Welcome to the August issue of Benerkenswert! And welcome back to our unofficial beginning-of-month schedule. We are continuing where we left off last week.

You find this issue here on my website, here in a German translation provided by Google Translate.

Same same but different

In Taiwan, you can stumble upon the German flag on the weirdest of places. In the logo of an inconspicuous breed between pharmacy and beauty salon, for example, as I wrote about last week. 80 years after the Germans tried to plant their flag on the whole world, this seems like an odd choice. What is it about Germany that leans itself to marketing? Is there something more to it? And is there something I as a German can learn from it? These are the questions that will still guide us this week!

A bit of home

The German-Taiwanese relationship is of course mostly one of business, politics, and personal friendships. But there are also some events that approach the general public. Here are some examples from my last two years.

German Christmas Market in Taipei, December 2021

Christmas markets are maybe one of the most important cultural institutions in Germany (slightly behind soccer matches but ahead of New Year Street Fighting and sunbathing nudists at FKK beaches or lakes). Coming here a year earlier, I was glad that there was a German christmas market in Taipei as well. The capitalization of these words is deliberate, the event was definitely more about Germany than Christmas. Instead of wooden lodges and fir trees and snow, we found shiny cars, product booths for Bosch and VW, German sausages and gluehwein. (Also bubble tea, of course, this being Taiwan!) It was clear that this was about manufacturing more than meals.

Bauhaus Museum Taichung, April 2022.

A small museum in the upper-class outskirts of Taichung, Taiwan’s second biggest city. The building was fittingly modern and minimalist and also a bit run down. We were invited for the opening. In the garden around the museum, there was a cute ceremony (with Pirates of the Caribbean-like music!) and cultural exchange over craft booths and DIY experiences. The exhibition itself was dedicated to the Bauhaus movement. If you think that Germany’s “engineering prowess” is only about machines you err. In the times before Steve Jobs, “industrial/functional design” was a very German discipline. Braun is the company typically associated with this. Maybe even Porsche if you look into the luxury segments.

These ideas had their origin in the “roaring 20s”. Bauhaus was an art school in Weimar back then that created a holistic philosophy around design, aiming to bring together different arts and to unify individual artistic vision with mass production. With its functional elegance, Bauhaus’ tenets like “form follows function” are now widely established modernist design principles that made not only Ingvar Kamprad billions (the founder of IKEA). While in the broad German public Bauhaus is often forgotten and sometimes wrongly associated with brutalist architecture or cutting corners, it is very alive in Taiwan. Here, it is appreciated as a historic ornament to a more holistic (and less explicitly fleshed-out) aesthetic around meaning, functionality, customer-focus, and quality.

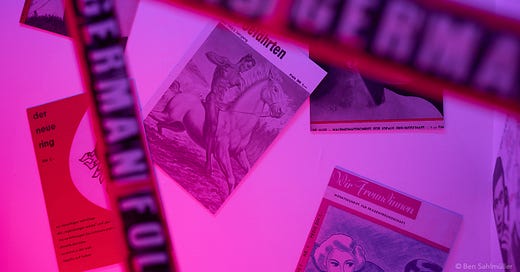

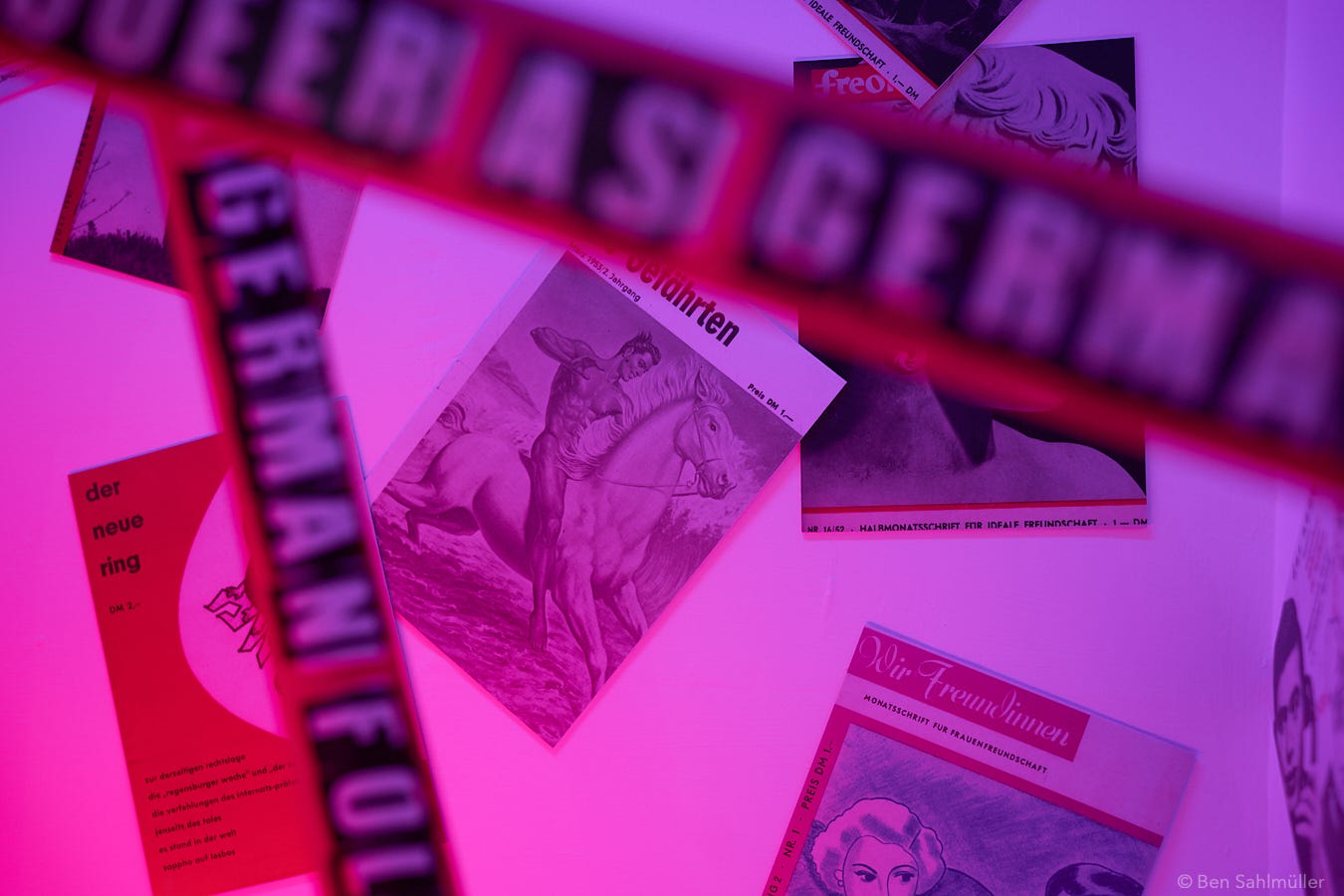

Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei, October 2022.

The brick house of somewhat colonial style features a small exhibition about the history of the LGBTQ movement in Germany. Photos, reports, and a few historic items reminded of the struggles for civic liberties and celebrated those who fought for them. There is a curious, respectful, somewhat hesitant celebration of the power of free sexuality in cities like Cologne and Berlin, and a proud and aspirational celebration of the gender equality achieved in Germany. (A topic that gained even more importance since, given a wave of MeToo allegations, a topic for another time).

228 Memorial, Chiayi, May 2021.

The New York Times (if I remember correctly) once named Germany’s most important cultural idea to be “Vergangenheitsbewaeltigung,” literally “coming to terms with the past,” “transitional justice” in more academic circles. Taiwan too looks back onto a complex, violent history after which oppressors and oppressed (or rather their offspring) try to live together peacefully. 228 commemorates February 28th (1947), when mass protests and subsequent massacres shook the country, starting a process that would lead to a more than 43 year long period of martial law know as the “White terror” era of Taiwan. In Chiayi just as in other cities, various memorials are dedicated to the day. (I wrote about many of the memorials in Chiayi in this report about a study tour I did in 2022.)

For the academic and civic community dedicated to this memory, the way Germany tries to come to terms with its past is an inspiration. Of course, whether or not Taiwan should follow Germany’s example like a “todo list” or find its own approach is often debated. But as “finding its own path” is often used by critics of the process as a euphemism for halting it, this debate is often an attempt to respect Germany’s struggle and live up to its underlying humanist values.

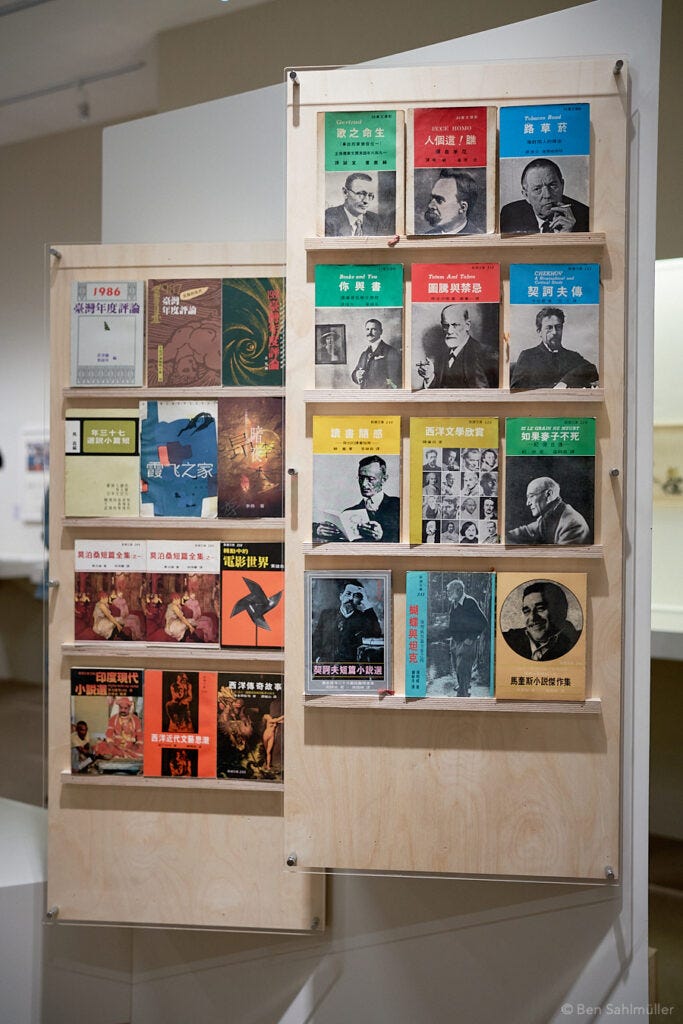

Various book stores, throughout the years.

You can often find German book covers or even German books in the various book stores in Taipei. Many German and German-speaking thinkers and artists of the 18th century and onward enjoy much respect, Nietzsche, Freud, many of the romantics come to mind, Schubert, Beethoven and other composers, Einstein and various scientists of course, authors like Hesse. (Women are much much harder to come by, unfortunately…) Most of them stand for an ideal of depths, wisdom, authenticity, philosophical integrity, and character. Not rarely, their books even carry its original German title – something I rarely saw with regards to Mandarin back home.

The German idol

There is a thematic thread that runs through all these examples, it’s the story of enlightenment, industrialization, and modernity, with its virtues of rationality, discipline, diligence, and responsibility. There are of course reasons for why this story of Germany’s progress is so appealing. Taiwan too has a manufacturing-based economy and Germany and Japan have long been the model students in this discipline.

But Germany’s power – or rather, the power of the idea of Germany – would not even be half as powerful if this idea would be constrained to the economic story. Indeed, there is a second thread running through these examples, the story of romanticism, humanitarianism, honesty, artistry and a virtuous character on the other.

Only together these two foundations make the story of Germany so inspiring and sexy. Not only its economic weight, but rather how it is connected to an idea of humanism and culture. It is a story of success, but of a success that still leaves room for questions of deeper truths and individuality, where it doesn’t push aside virtue and character, and if not happiness then at least meaning. “Germany” then is an idol of success both in the global economic arena as well as on the individual, societal, humanist scale.

Made by Germans, once again

For me as a German it is easy to identify with this idea, as I grew up with these stories as well. It is maybe too easy, and it is this “too easy” that tingled my spider-senses. The story is just too well aligned with the image Germany likes to have of itself.

Then I realized that this is not a coincidence. The idea of Germany I am confronted with lies at the center of Germany’s soft power, but not as its source, but an implementation thereof; not as the underlying truth but as the way a story is told. The German cultural events mentioned above were supported by the German Goethe Institute (the Bauhaus and LGBTQ exhibitions), the business events by its Trade Institute (the Christmas Market), even personal experiences often built on scholarship programs supported by the German government or state-supported non-profits.

The idea of Germany I see here is not “made in Taiwan”, it is not a neutral view from afar, it’s not an accident. The idea of Germany prevalent here too is “made in Germany”, or at least supported by the Germans in Taiwan, and the small flags hanging around show that this approach works!

There is one reading of this where Germany’s image is just a successful advertising campaign the Taiwanese greeting me in the streets fell for. I think this reading is cynical and wrong. Of course, the real Germany is much more chaotic, multifaceted and alive than its cliché. But despite the marketing or cultural dialogue, it would be cruel and wrong to describe the image Taiwanese have of Germany as “shallow” or “naive”.

Rather, I’d call it “romantic.” Taiwanese are not nascent towards Germany’s historic atrocities, but they are also not ignorant towards a nation that tries to make amends and tries to find strength in its complex history. (Like everything, even the way the world wars are seen is more complex, of course. The historic narrative in Taiwan about its own history is more one of living under oppression of a regime, compared to the German one which sees itself stronger as part or enabler of that regime. This also means Taiwanese people usually don’t project the same level of shame onto Germans that some Germans might have felt themselves when confronted with their history.) The core of the message often meets not cynicism but genuine appreciation, because it resonates with an aspirational image Taiwan has of itself – as a country eagerly trying to overcome its challenges. I must confess that I too am tempted from time to time to wallow in this romanticism.

Brotherhood is about more than cars

There lies a dark irony in all this. In the decades following the world wars, Germany much more than other Western countries built its foreign policy on its civil society. German organizations like the GIZ are internationally respected for their development work, the German Goethe Institute for its cultural bridge building. German parties have a strong network of international institutions to build their networks and knowledge. (I wouldn’t be here otherwise).

And yet, as the economic boom of the 20th century wears off, the German soft power approach begins to stutter. In much of Europe, these organizations struggle to overcome the dark shadow of German history and heavy handling of European politics. In much of Africa, there is little they can do to overcome the image of the colonizer and to compensate for missing developmental support. In China, German civil society’s highlight on human rights issues is a nuisance. At best, it provides the party and its controlled enterprises with welcome leverage to wrest economic concessions from its German counterparts.

Thus, in the age of American cultural hegemony, Germans see their soft power attempts wane. In this approach, cultural efforts are a mere marketing campaign to strengthen the “made in Germany” brand – and have to justify themselves as such (economically). German ambassadorship then is not built on its culture, but cars. This is maybe even more true in Taiwan, the most important country without an official ambassador.

The irony is that in Taiwan maybe more than in other countries, an honest cultural approach could actually work! In its way to development, Taiwan is a success story like few others. Last century, it was a dictatorship with little cultural significance and economic power. People used to manufacture umbrellas at home as this was a product that required little machinery. (The British Crown still uses umbrellas made in Taiwan by the small manufacturer Jiayun Umbrella Company Ltd). Now it is one of the most developed countries in the world. But of course this journey was rough, with setbacks, and a high price. Germany after starting with an advance of miles, was for a long time still a few steps or half-steps ahead of Taiwan (in a naive but good-enough understanding of “progress,” that is) and thus acted as a role model for global leadership in manufacturing, as a respected member of the global community, for its cultural significance, civil rights and liberties and its quality of life.

Thus, Taiwan and Germany both follow a similar economic model (dependent on manufacturing and exports with strong weaknesses in financial and digital services). But as the stories about Germany show, both societies also have a similar cultural foundation based on more classic modern and liberal values.

Or at least both had a similar foundation, if both societies would indeed try to live up to these values. Is the Taiwanese interest in Germany’s struggle to become a liberal society authentic? And does Germany itself still live up to the values it likes to propagate abroad?

More on that in the next issue!